Download Planning Insight

The views expressed are those of Anchor Capital Advisors, LLC (“Anchor”) and are subject to change at any time. They are based on our proprietary research and general knowledge of said topic. The below content and applicable data are in support of our views on said topic. Please see additional disclosures at the end of this publication.

If you are considering a move to a new state or have recently relocated, you are not alone. According to a recent study, an estimated 23 million Americans moved to a new state in 2021; a more than 20% increase when compared to 2020.[1] This is hardly surprising given the rise in cost of living and remote work opportunities, both heavily influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The following aims to help you navigate a relocation and highlights the below topics for your consideration:

- Understanding domicile and residency, noting states will have varying definitions

- Recognizing the tax implications of establishing domicile, whether deliberately or inadvertently

- Discussing best practices when relocating and dealing with a domicile audit

Whether your move is attributed to the pandemic, proximity to family, a preferred climate, or simply to take advantage of more friendly state tax laws, it’s critical to be mindful of the considerations that go into establishing residency especially as states don’t like losing taxpayers.

Since the onset of the pandemic, we saw many states issue guidance on relaxing their residency enforcement while executive orders were in effect. This allowed people to work remotely out of state without complicating their tax profiles. Eventually the executive orders expired, and those same individuals found themselves inadvertently establishing tax residency in higher-tax states.

DEFINING TAX RESIDENCY

The definition of a resident will vary between states, so it is important to understand the classification for both the state you are attempting to establish residency in, as well as the state you are attempting to leave. Generally, states will define a resident as someone who is domiciled in the state, or someone who has established statutory residency. Massachusetts follows this definition, per TIR 95-7.[2] Most individual’s domicile residency and statutory residency are the same, but the distinction between the two can become very important for those moving or those with connections in multiple states.

Statutory Residency

Massachusetts defines this as someone who “maintains a permanent place of abode in the commonwealth and spends in the aggregate more than one hundred and eighty-three days of the taxable year in the commonwealth”.[3] Most people are familiar with this concept and the idea of counting days (i.e., tracking time spent in a new location), though there are some nuances.

- Permanent Place of Abode. The Massachusetts Department of Revenue states that a permanent place of abode is a “dwelling place continually maintained by a person, whether or not owned by such person”.[4] This does not include situations such as camps, dorms, a place completely lacking both kitchen and bathroom facilities, a place that is not winterized, or a hotel room (depending on the circumstance).

- Days Test. When counting days spent in a particular state, it’s important to note that partial days, and even instances of traveling through a state, will count as one full day. Exceptions to this rule are military personnel on active duty or individuals receiving medical treatment for an extended period of time.

Domicile Residency

While you can be deemed a resident of multiple states, you can only have one domicile. Practitioners often define domicile as a “state of mind”, or the place where one would return home to after an extended absence. This may seem somewhat subjective, and it is ultimately based on a fact pattern that considers all personal, economic, and social matters. The below non-comprehensive list includes some common factors, as an example:

- Personal.

- Location of Personal Residence

- Location of Family

- Time Spent in State, As Compared to Other States

- State of Voter Registration o State of Vehicle Registration

- State of Driver’s License

- Location of Medical Professionals, Accountants, Etc.

- “Teddy Bear Test” – i.e., Location of Near and Dear Items

- Economic.

- Location of Workplace

- Location of Bank Accounts

- Location of Real Property & Investments

- Social.

- Location of Volunteer Organizations

- Location of Club Memberships

- Location of Place of Worship

The factors taken into consideration can be quite wide-ranging, however what matters is the strength of ties to a state, not the number of ties.

TAX IMPACT

Most states will follow what is called a worldwide taxation regime, meaning they will tax their domicile residents on their total income, including portfolio income, regardless of where the income was earned. This can have a substantial impact on individuals moving from higher-tax states to lower-tax states, or vice versa, and as such correctly establishing domicile in the intended state is critical.

For individuals who are dual residents, they may find themselves with two states subjecting them to taxes on their total income. To mitigate a double taxation, states will generally provide tax credits for amounts paid to other jurisdictions. With that said, states have varying rules which may not result in a dollar-for-dollar credit. For example, New York provides tax credits for taxes paid on earned income (i.e., wages) to other states, but not for taxes paid on investment income. Typically, the domicile state will get the “first bite of the apple” for tax purposes.

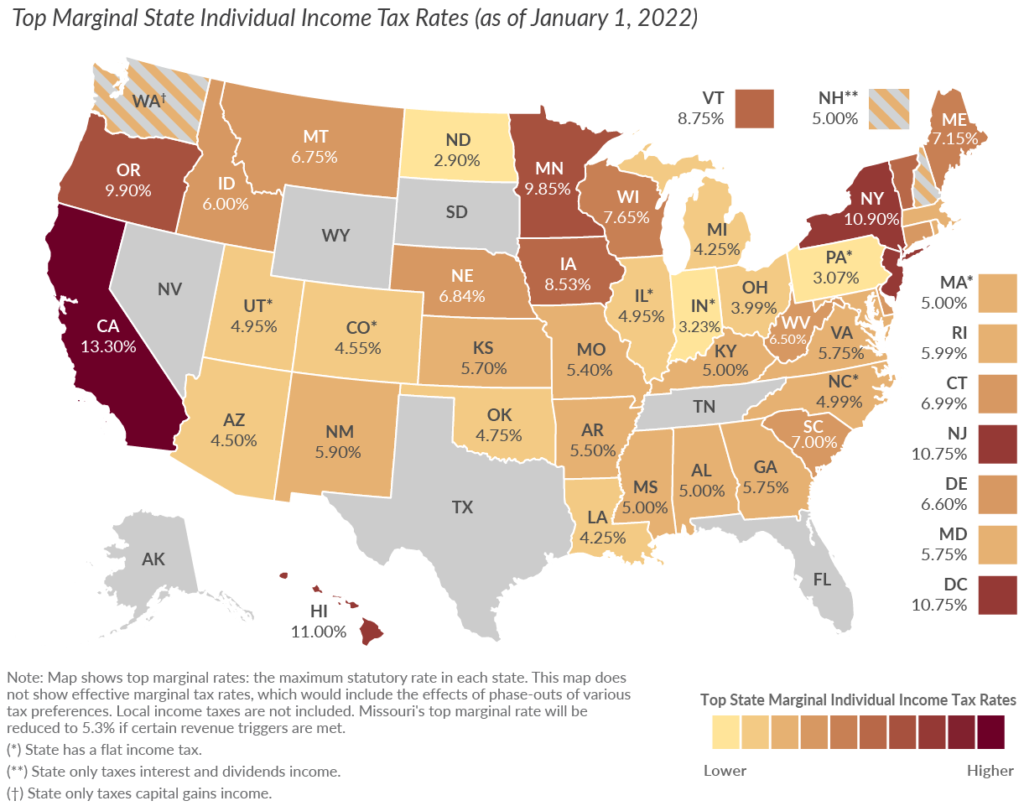

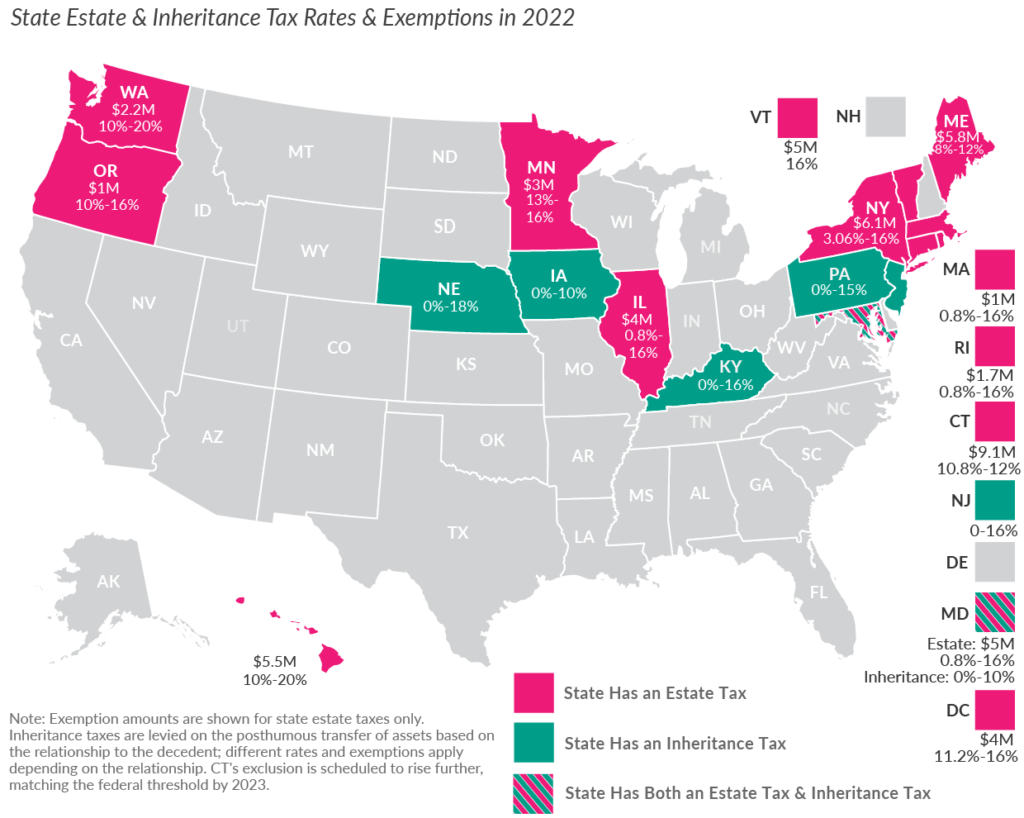

For reference, the below maps [5] illustrate the income tax rates by state, as well as the states which have an estate or inheritance tax:

BEST PRACTICES

Escaping the New England winter for sunny Florida sounds enticing, but for many, escaping the Massachusetts state tax for Florida’s lack of state tax is much more appealing. As Americans head for states with a lower cost of living at an increasing rate, states are also becoming increasingly more frustrated with losing taxpayers.

To combat this, states can issue domicile audits, an arduous process where individuals bear the burden of proof in demonstrating their residency status is legitimate. States like Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and California are considered aggressive auditors on this topic. Call logs, credit card bills, and E-ZPass charges are often combed through as part of the process. One recent audit in New York was even partially decided based on where the taxpayer’s dog visited a veterinarian, and auditors have even reportedly visited individuals’ residences to check their refrigerators when determining whether they were full-time residents or not. While these examples may seem extreme, defining a domicile is subjective and New York will typically end up winning over half of their audits.[6] It is also relatively common for an audit won by the state to result in subsequent audits in the following years.

You should consult a specialized tax advisor when dealing with a domicile audit, however the below are some best practices that can help you “leave” your former state for tax and record-keeping purposes:

- New Residence. You should be able to prove you have a residence elsewhere, whether by way of a new home purchase or new lease agreement.

- Intention. You should be able to prove you intend to reside elsewhere, for the time at least. In other words, the fact pattern cannot suggest you are simply away for an extended period with the expectation of returning.

- Abandonment. You should be able to prove you have abandoned your former state. Some common examples of this are selling or renting the former residence, re-titling vehicles in the new state, registering to vote in the new state, engaging new medical professionals, and filing for the new state’s homestead exemption.

Additionally, it is important to note that each state has its own laws regarding estate planning and administration. Once a new domicile is established, it is critical to update any basic estate documents (i.e., Last Will & Testament, Revocable Trust, Durable Power of Attorney, Health Care Proxy) to ensure they are in compliance with state law.

HOW ANCHOR CAN HELP

Establishing domicile in a new state, or avoiding it, is a process that requires more time and consideration than simply counting your days in another state. As relocating is onerous by itself, your Anchor team will help review your situation and provide guidance along the way. Contact your Private Client Advisor to help design the best strategy for you.