The views expressed below are those of Anchor Capital Advisors, LLC (“Anchor”) as of the date written on the last page of disclosures and are subject to change at any time. They are based on our proprietary research and general knowledge of said topic. The below content and applicable data are in support of our views on said topic. Please see additional disclosures at the end of this publication.

Activist investors—shareholders who refuse to remain quiet when they believe companies they own are going astray. They confront company management and corporate boards, fighting proxy battles and pushing for change on behalf of shareholders. The press can portray these activist investors as if they were Viking raiders—vultures who swoop in, plunder enterprise value, and make a hasty retreat before management can stop them. We believe the truth is very different; that many executives and boards may be motivated by interests that conflict with those of shareholders. When that happens, someone must take action.

At Anchor Capital, we don’t proclaim ourselves to be activists. However, we are long-term shareholders with a fiduciary duty to our investors. In discharging that responsibility, we strive to ensure that company resources are being effectively deployed to maximize shareholder value. In particular, we examine five key metrics to assess whether managers are acting in shareholders’ interests:

1. Are management’s compensation and incentives aligned with company performance?

More often than not, we see management compensation increase year after year. In some cases, management is well compensated even though the stock has underperformed its peers and the broader market. IBM was the poster child for dispersion between stock price and management compensation. Between 2012 and 2017 IBM reported 20 quarters of declining year-over-year revenues (including acquisitions), 15% year-over-year decline in earnings and a 23% decline in free cash flow. Yet IBM “beat” on earnings, because financial guidance to analysts had been set low, and it used lower taxes and stock buybacks to “exceed” the expected number. IBM’s stock price had declined by 26% over that same time period while the S&P 500 had increased over 85%. Meanwhile, IBM’s CEO, Ginny Rometty, had her executive compensation increase from $20 million in 2015 to $33 million in 2016.1 By the end of 2017, the Board recognized the company and stock underperformance and adjusted Ginny Rometty’s compensation accordingly.

Our focus is to find companies where management teams and boards are incented to look out for the interests of the shareholders. That means executive compensation should be tied to financial targets that ensure healthy growth for the company. We routinely ask our management teams what metrics they watch and which ones they are compensated on. The metrics that are important to us as shareholders include organic revenue growth (excluding acquisitions), return on invested capital (ROIC) exceeding the cost of capital, appropriate use of leverage and growing free cash flow. When we believe we see misalignment of interests, we review and vote the proxy statements as we deem appropriate and engage the board compensation committee.

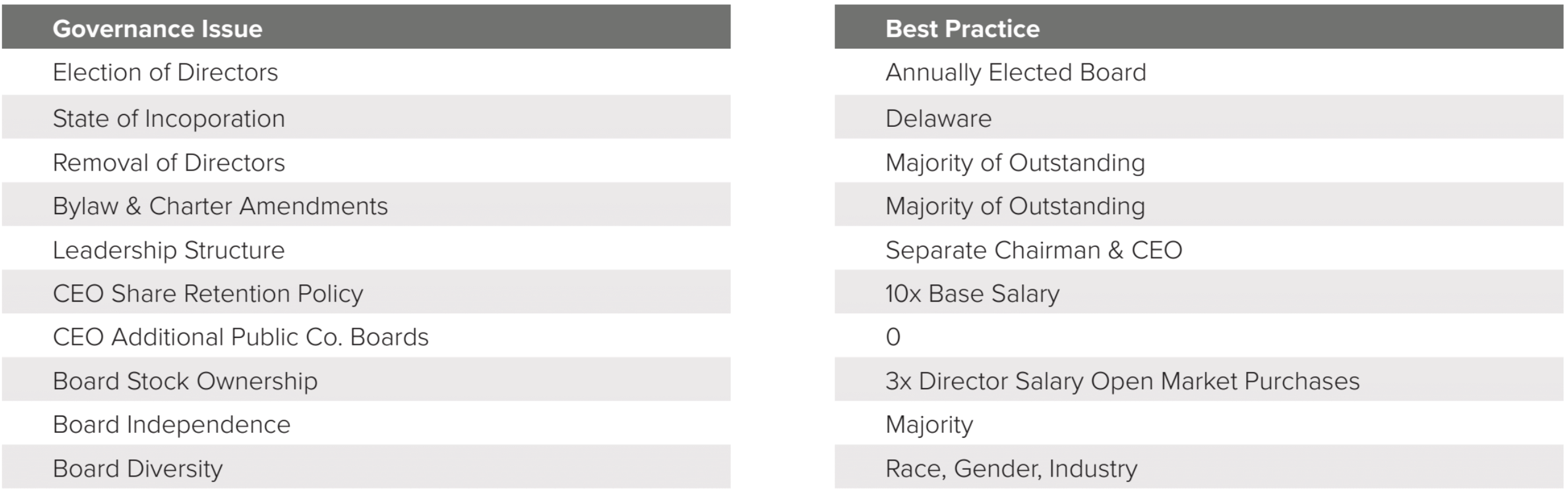

2. Does the board’s structure follow best practices for corporate governance?

The board of directors plays an important part in public oversight of a company and ensuring that shareholders are protected. At Anchor, we look at a number of measures around corporate governance, striving to ensure that the companies we invest in follow corporate governance best practices. We vote proxies, talk with boards, and work with other investors to make sure companies are following sound corporate governance principles. A well-functioning board incorporates risk management and enables managers to set the appropriate strategic direction for the company.

3. Is the company’s capital allocation sustainable?

Another area of importance to investors is a company’s capital allocation policy. We strive to understand how the companies we own utilize their free cash flow. Companies have a choice in how they allocate capital at different points in their life cycle. Early-stage companies spend more on reinvesting in the business, capital expenditures and potential acquisitions. More mature companies are expected to return cash to shareholders through dividends and share repurchases. We spend a significant amount of time assessing whether a company’s current capital allocation plan can continue, or if it is at risk of cuts due to a declining business. Part of our total return strategy includes dividends and share repurchases.

4. Is management doing enough to cut costs?

Activist investors focus on cutting costs and improving operating margins as ways to increase earnings and cash flow. Some companies struggle under the weight of bloated cost structures or layers of management that add nothing to the growth of the firm. Others take cost cutting seriously–and achieve impressive results. For example, after Kraft spun off Mondelez into a separate company, Mondelez as a standalone company employed zero-based budgeting to reduce costs and become more efficient.2 CSC merged with a spinout from HPE to form a new company called DXC; it focused on reducing the layers of management and executive perks that were emblematic of HP’s culture. These moves added 3% to 8% to the operating margins.3 We are advocates of pushing management teams to rethink costs, because cost savings flow through to the bottom line and ultimately benefit shareholders.

5. Does the company’s acquisition strategy make sense?

CEOs feel pressure to grow—and that can mean spending on acquisitions and capital projects. If the management team is unfocused, their acquisitions may prove too expensive or distracting. They may also fail to add value, or even mask underlying problems in the business. When looking at companies to invest in, we look at the management team’s demonstrated history of making acquisitions. Were the acquisitions well integrated? What is their valuation? Were they accretive both strategically and financially? Coty is one example of a company with an unimpressive acquisition track record. It acquired Procter & Gamble’s Specialty Beauty Business at high valuations4 and excessive debt before going on to underperform its peers and the broader stock market.5 We challenge management teams to prove whether they are making acquisitions for the benefit of shareholders—or purely to cover up a lack of growth or direction in the business.

Searching for value while advocating for investors

There are a variety of ways to increase total shareholder return. At Anchor Capital Advisors, our goal is to look for quality businesses that generate value over long periods of time. We find that shareholder-friendly companies that focus on the right metrics tend to outperform the market in the long run. We may not be “activists” per se, but we believe it is our responsibility to push for best practices at the companies we invest in—for the benefit of all investors.

Click here to download a PDF of this article.